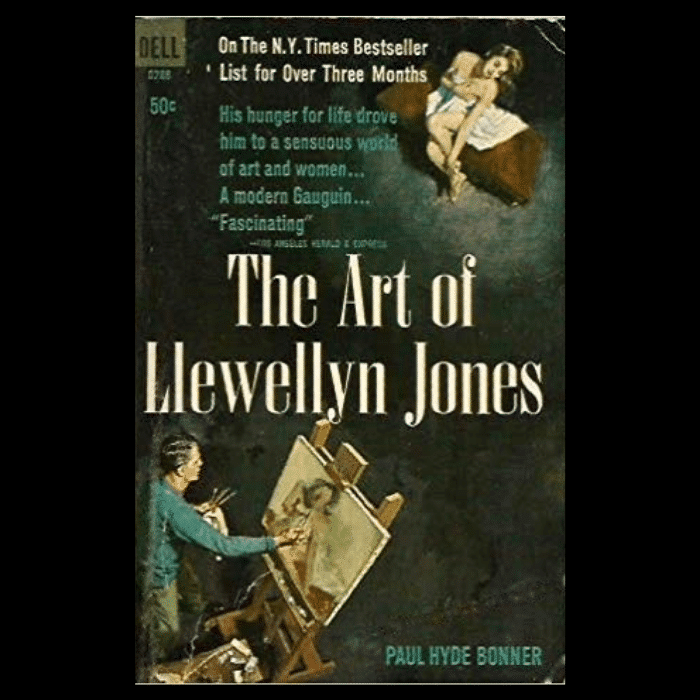

“It’s ironic that Hulings was the illustrator for a book cover that romanticizes what it is to be an artist.”

There’s a myth that being an artist involves getting away from it all. An artist’s identity might seem to be a delicious escape, and there’s a fair amount of fantasy in the culture to support that. When you think about the mystique of Paul Gaugin—who is mentioned in the quote on this cover for a mass market paperback about a disappearance into a new life as a painter—his artistic lifestyle seems to have been one big fruit-laden tropical adventure. Or maybe you dream about how great it would be to be Gene Kelly’s character in an American in Paris, dancing through cobblestones with a baguette and a paintbrush, ready to fall in love and then find a rich benefactor to buy his art.

Double-Life

The Art of Llewellyn Jones borrows this kind of escapist storyline—mostly from The Moon and Sixpence, in which Somerset Maugham fictionalizes the life of Gaugin as a London stockbroker who abandons everything for Tahiti. In this novel, the seemingly conservative former ambassador to Belgium disappears. When he re-emerges thousands of miles away, he has a new name, a new accent, and a new bank account—and he’s a painter. His adventures in painting eventually take him to France, and there are plenty of wayward women in his new lifestyle. Author Paul Hyde Bonner became a second lieutenant in the US army 1917-19 and later served as the special advisor to the United States ambassador to Rome. Bonner evidently knew the restraints of the diplomatic life and lived vicariously through his protagonist.

Painting Within a Painting

Hulings’ cover has an evocative layout, with the title lettering occupying the diagonal open space between artist and model. The lighting is almost theatrical, with round pools of illumination on each figure. It’s satisfying to see the depiction of the artist’s work-in-progress: Hulings has shown the painter just starting to block out the highlights and shadows. It’s contrasted with the subtlety of the values on the skin of the “real” woman, making her comparatively luminous and lifelike.

24/7

It’s ironic that Hulings was the illustrator for a book cover that romanticizes what it is to be an artist. Hulings himself abandoned a career as a successful illustrator, pulling up stakes in New York and heading to Europe for almost three years of study, drawing, painting, and wandering from the Arctic Circle to southern Egypt, to “turn himself into an easel painter.” Hulings was not escaping, however. He was already a hard-working artist. When he returned to the States, he launched his fine art career but continued to work in illustration until he could support himself fully with gallery sales.

As an exceptionally pragmatic and business-minded steward of his career, there’s nothing fantastical about how Hulings developed his skills or managed his professional relationships. He worked tirelessly at his craft and at his business. Today his legacy is two-fold: an impressive oeuvre that rightly places him at the pinnacle of American artists, and The Clark Hulings Foundation for Visual Artists, a non-profit organization that provides today’s artists with the tools, training and peer support to build their own self-sustaining businesses—so they, too, can fill the world with art.

While it’s to fun to read otherwise, being an “Artist” is not a way to “get away from it all,” but in fact, a calling to be of lifelong service to the heart of creativity, community, and economy. When we look at Hulings’ work, we are certainly glad he rose to the challenge.

The Search is On

Many of the original illustrations for Hulings’ mid-century book covers have so far escaped our archives. Let us know if you know where this one is.